Years ago a bunch of retired USMC brass decided the Marine Corps needed a world-class museum. They created an organization, gathered up a lot of private money and hired the best design firms. When it was done, they turned the whole thing over to the Marine Corps Historic Division.

The result is a giant saucer-shaped structure of concrete, glass and steel with earth berms around the sides, an impressive formal entrance, and a glass spire/teepee that can be seen for miles in all directions. It has a curious lean to one side and a giant American flag flying from its pinnacle. It’s bewildering at first until you recognize the abstracting lines of the Iwo Jima flag-raising statue (which I find very moving).

The Museum is located in one quadrant of an intersection at the entrance to the sprawling Quantico Marine base south of Alexandria, Virginia. Quantico is the brains of the Marine Corps, where all the schools and all the theoretical developments are born.

Alma Mater

I was drafted out of college in 1969, the height of the Vietnam War. I was torn between a family tradition of military service and a childhood diet of war movies, and my belief that the war was unjustified and had gone badly awry. This was in the wake of the My Lai massacre. But in the culture of my childhood, artists were not respected as real men. I decided I would initiate myself into manhood by acquiring the credentials of a Marine and a combat vet so that I could feel good about being an artist.

When I learned in 2005 that the Marine Corps was building a shrine to its history that included murals in the exhibit work, and that it was at Quantico, where I went through Officer Candidate School and Basic School, I did everything legally possible to make sure I got the job. Fortunately the company I was bidding under, ThemeWorks in Florida, landed the exhibit contract and subcontracted the murals to me. I was overjoyed.

The plan of the Museum is a gigantic doughnut with a central rotunda capped by the glass spire. Around its periphery were the hallways and exhibit spaces. The first half of these spaces would be used as staging areas for the materials we needed to complete the second half. So when the Museum opened in 2006, it covered Marine Corps history from the beginning of World War II to the present. Later they would complete the first half of the Corps’ history in those staging spaces, the history from 1775 up to WWII.

The Recovering Marine

On my first day at the job, I was introduced to retired Colonel Joe Long and retired General Ron Christmas. I jokingly described myself as a “recovering Marine.” Both men frowned, and I was momentarily paralyzed with Boot Camp fear.

“I’m not sure I like the sound of that,” said the general. I had to think fast.

“You mean you didn’t have to go through that twelve-step program where you learned how to deal with those slack-ass civilians again after you retired?” I asked.

They both laughed, and I breathed easier.

“Should I refer to myself as a former Marine?” I asked.

“No,” they said in unison. “Once a Marine, always a Marine!”

“Damn, does that mean I still have to pass the physical fitness test?”

“No,” General Christmas said, “just turn out some good murals, or you’ll be doing push-ups ’til you puke.” He wasn’t smiling, but Colonel Long was.

Getting It Right

I did turn out some good murals, probably the best I’ve ever done, and I did research way beyond what the design firm asked of me because I knew that there were hundreds, maybe thousands, of veterans who would see the most important event of their life represented in the exhibits we were producing, and we owed it to them to get it right.

The job took several months and several months to complete. I had to paint the scenery on some huge walls, go home, and let ThemeWorks build the three-dimensional rocks, sandbags, and buildings in front of the murals, then come back and make sure everything flowed undiscernably from the 3-D to the 2-D. Some of the Vietnam-era, Korean DMZ and Battle of Seoul murals were moderate in size, but there were three that stood out as exceptional.

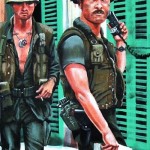

Battle of Hue

The Battle of Hue exhibit required a mural that continued the wall of the ancient citadel, the traditional capital of Vietnam, extending into the distance and across from it was a line of houses with heavy battle damage. It featured a squad of Marines on the residential side of the road. Since the Museum asked me not to sign the murals, the exhibit designer’s rep suggested I paint one of the Marines as myself. I wasn’t at the Battle of Hue but I had pictures from 1971 of me talking on the radio, so I snuck my “signature” in that way.

Tok Tong Pass

The Battle of Tok Tong Pass was a pivotal event in the Marines’ experience in Korea. Visitors walk through a plastic curtain into a freezing-cold room. It’s night. Beneath their feet is a muddy, ice-covered road. Along one side is a rocky, snow-covered slope with startlingly realistic figures. One hears the voice of Captain Bill Barber on the radio as a corpsman bandages one of his three wounds. A mortar team and some riflemen huddle behind the stacked, frozen, Chinese dead as Barber’s roughly 150 men try to hold off 3000 assailants.

My job was to carry the illusion of the snowy slope up into the darkness above and to create the illusion of distant hills on a panel set further back from the viewer. Sound and light effects, flairs and tracer rounds, mimic the battle.

Hill 881

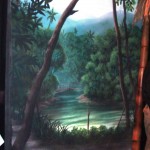

The crowning achievement for me was a 120-foot by 20-foot tall cyclorama of the siege of Hill 881 South near Khe Sahn in Vietnam. To get it right I contacted many of the survivors and got copies of their personal photos. I was particularly helped by Carlton Crenshaw, who was the artillery officer for the Hill, and by retired Colonel Bill Dabney, who was the commanding officer during seven months of perpetual bombardment by the surrounding North Vietnamese Army.

Visitors walk through the body of a CH-47 cargo helicopter and down the ramp onto the fire base. Around them are sandbag emplacements and figures, some manning guns, some helping the wounded onto the helicopter, some getting the last rites. A 105-millimeter howitzer in a circular sandbag emplacement has both tires flattened by the perpetual spray of shrapnel. A large rat can be seen inside one of the tiny bunkers. Surrounding the visitor is an accurate recreation of the crater-scarred landscape in all directions. Visitors exit the exhibit by going through the command bunker, where they find a video display of Bill Dabney describing his experience.

During the job I decided to donate all of my War memorabilia to the History Division. To my delight, they put on display in two small cases a C-ration meal I had from 1969 and a pair of dog tags hanging on a chain along with a peace sign made from a hand grenade ring and two cotter pins. Peace signs like this were produced for the whole platoon by my radio man with the pliers of his repair kit. Regrettably, I wasn’t able to attend the Grand Opening of Phase One due to other commitments.

Phase Two

Two years later I learned that the Museum was ready to complete the first half of its history. This time ThemeWorks did not win the contract. Design Craftsmen in Michigan got the nod and had their own muralist. I was despondent. Then some large corporation bought Design Craftsmen and ran it into the ground for a tax write-off. It was the willful destruction of one of the best companies in the business, and it left the Marine Corps in the lurch. I don’t know how it was settled in court, but ThemeWorks was back in the picture, and so was I.

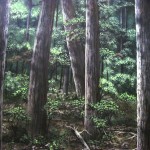

The square footage of the next phase was perhaps twice the size of the 2006 effort. This time we recreated Belleau Woods in Belgium in World War I with a lot of trees and four long murals in which the verdant forest gradually becomes a lunar landscape of craters and trenches. There were smaller murals and four miniature dioramas, one of them requiring a recreation of the Harper’s Ferry Arsenal and John Brown’s capture by the Marines, under the command of Army Colonel Robert E. Lee, prior to the Civil War.

In another diorama, I had to paint the Battle for Cuzco Well in Cuba in 1898. This required recreating the landscape with only a contour map and some pictures of similar desert environment for guidance. As I was installing the mural, a retired warrant officer from the combat artists’ section appeared with his personal photographs of the site from his time stationed at Guantanamo Bay. To my delight the diorama mural matched the photographs almost exactly except for some protruding rocks not shown on my map.

I made sure I was able to attend the Grand Opening of Phase Two. I rented a tux and the Museum assigned an attractive young docent to be my escort. I realized quickly that, despite all the hours I had spent working in the Museum, I had never seen the completed exhibits. My escort was a font of information and personally knew many of the surviving veterans of particular campaigns.

All Marines were in their dress blues. The President’s Marine Band (more accurately called an orchestra) wore red. The food and champagne were “outstanding,” to use a Marine term, and I had the pleasure of hearing it used again in reference to my murals by the Commandant and Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps.

The new commandant, at least eight feet tall, was the first one young enough not to have earned his combat action ribbon in Vietnam but rather in the Balkans. The Sergeant Major, whose entire sleeve was covered with stripes, was a short, black Marine whose bearing was every Marine recruit’s worst nightmare.

P-38s

I got to ask the Commandant something I had always wondered about.

“Do you carry a P-38 C-ration opener on your key chain like the rest of us?” I asked. (No Marine Corps survivor can be away from his P-38 for long without hyperventilating.)

“No,” he said, “that’s what I have the Sergeant Major for.”

The Sergeant Major’s severe demeanor broke into a grin.

Semper Fi

I’ve never really understood why the Marine Corps motto is “Always Faithful.” Faithful to what? The ideal? The country? The Corps? Each other? Probably it’s all of these, but the strongest is the last one. I gained a lot from my Marine Corps experience, and this was an opportunity to give back. The Museum has gone through many changes in the last few years, and not just updating to include newer conflicts; it was hit hard by the covid pandemic shutdown, as were most other museums.