In late 2011, the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago asked me to repair a number of deteriorating murals in their primate building and aviary.

The large, open flight room in the aviary presented a challenge in terms of gaining safe access to the higher reaches. I found that I could get up into the steel trusses under the translucent barrel vault over the flight room by way of a narrow catwalk which ran down the spine of the building. With a ball point pen, I was able to stretch out one of the holes in the steel mesh which kept the birds from being able to roost in the trusses and slip a ¼ inch steel cable through it into the space below. Then I clamped the top end to a truss member so the cable could serve as my safety line.

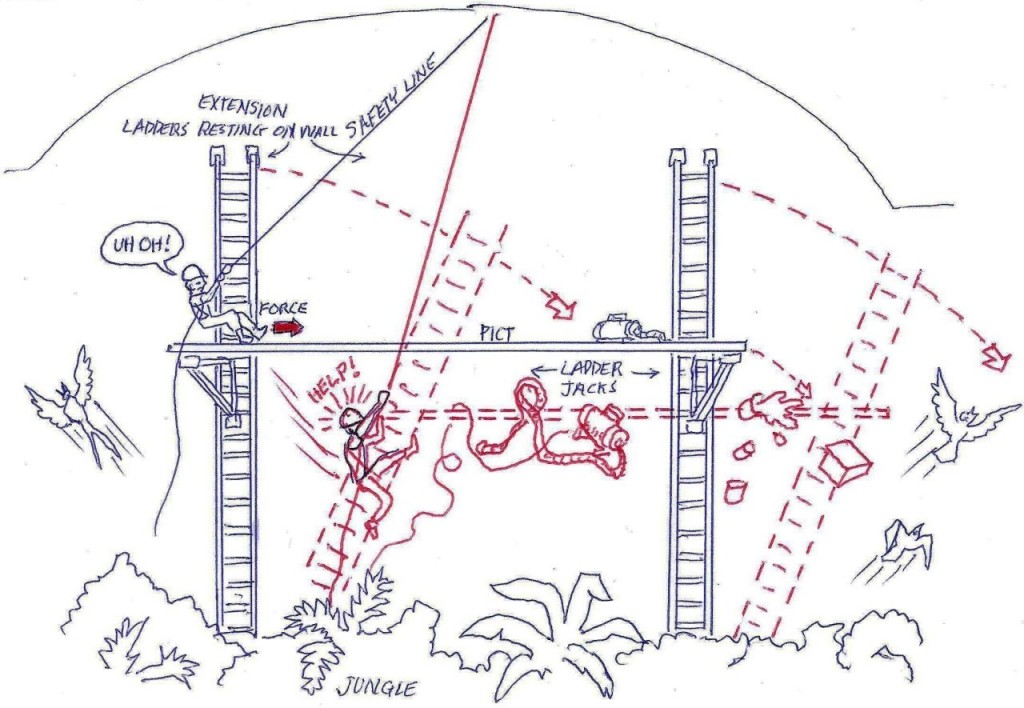

I set up two extension ladders about 25 feet apart against the tall wall at one end and set a painter’s pict, a narrow, extendable aluminum platform horizontally between supports called ladder jacks which stuck out from the two extension ladders. The finished rig was very bouncy and unstable so I was glad to be able to wiggle into a body harness and hook onto the safety cable hanging from above. To test the harness, I stepped off one of the ladders and swung around in the air for awhile, ala Peter Pan. I threw my cell phone to one of my friends in the facilities department who took a few pictures of me striking dynamic super hero posses. Later another friend who is a wiz at Photoshop, took out the ladder, harness and cable and voila, the Flying Muralist!

The painting went well on that end of the aviary, but I was really grateful to have the safety line when I moved the rig to the other end of the flight room. After getting the ladders and horizontal pict into place, I climbed one ladder, taking up slack in the safety line through the cable pinching device in the harness. I managed the difficult climb up and over the extended ladder jack and slid onto one end of the pict on my stomach. After a week or so of hard climbing, I was tired, so I rested. A thought drifted into my mind. If I had an unexpected fall, the safety line would catch me, but would I yell? And what would I yell? “Look out below!” or maybe “Headache!” which a lot of construction sites expect you to yell if you drop something heavy on the guys below you.

I struggled to my feet but made a big mistake. I used the safety line to pull myself up to a standing position. Since the safety line hung from a point above the center of the rig, pulling on it from one end of the pict had the effect of pushing it the other way which pushed both of the ladders, which were leaning against the walls, sideways. The tops of both ladders began sliding over in great arcs across the wall headed for a flat landing as the pict dropped from under my feet, along with several cans of paint, my spray gun drive unit, hose and extension cords. Before I could think up what to yell, the reptilian part of my brain took matters into its own hands and I heard myself bellow a terribly unique and clever cry: “HELLPPP!!!”

The ladders fell, one atop the other, into the jungle plants below, taking down a few small trees and the pict landed on top of them with a deafening metallic crash, scattering birds like the blast wave from a nuclear weapon. As I watched from above, swinging gently, suspended like a kitten carried by the scruff of his neck, large leaves fluttered down onto the tangled crash site.

Then the facilities crew on the ground swung into action, trying to get one of the ladders raised to get me down. The fellow who had taken the “Flying Muralist” photos earlier held onto the bottom end of my safety cable to stabilize me. But soon he discovered to his delight that he could move his hand in a small circle and cause me to spin like a performer in Cirque du Soleil. I threatened to drop my hard hat on him if he didn’t stop. He just grinned and asked me to drop him my cell phone. He said I could call the photos, “The Crashing Muralist.”

Safety

Much of my work is in conjunction with construction, which implies a certain amount of danger. This means wearing a hard hat, serious boots and protecting one’s lungs from overspray with a filter mask. But having to work as high as six stories means dealing with life-or-death issues. Researchers who climb the majestic redwoods and sequoias consider any fall from above 50 feet to mean certain death, but they are landing on a thick, spongy mat of leaf litter. Landing on a concrete floor from as low as six feet can cause permanent injuries.

When I was in a Recon unit in the USMC, one of our tricks for getting a team into inaccessible areas was to have a cargo helicopter hover about 100 feet over the ground and have us do “free fall” rappelling from four exit points down to the ground. The Corps’ emphasis on safety was fierce and left an indelible impression on me. In later years I used what I’d learned to teach rappelling, usually down a cliff face, to friends and to my elementary students in British Columbia, without a single injury. In more than 30 years of working at dangerous heights, I’ve only had two significant falls, both the result of an extraordinary series of circumstances, and in both I walked away without injury, for which I thank the Marine Corps for its obsessive attitude on safety.