Long ago in a galaxy far, far away — 1990 to be specific — I landed my first mural job for a zoo. I’d been working in various capacities for a custom cabinet-making shop in Kankakee, Illinois, for several years, and doing residential murals on the side for the interior designers who commissioned the cabinetry. A prop company in Milwaukee heard about me and asked if I would join them in bidding on the exhibit murals for the upcoming rehab of the aviary at the Milwaukee County Zoo, less than two hours from my home.

“Zoos have murals?” I asked. Who knew?

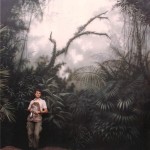

The job was gigantic: a dozen or so enclosures about the size of a large dining room, but several walls that were 30 feet high and hundreds of feet long. I was more than a little intimidated but I figured, “No guts, no glory, yah?” That kind of thinking has gotten me into more than one adventure/disaster.

At about the same time the owner of the cabinet shop confided that he was about to go under and, if my mural painting sideline was a lifeboat, this would be a good time to start paddling. It would prove to be a pivotal juncture in my story.

Then a stroke of luck, or maybe it was a sign from my career advisor/guardian angel that I was headed in the right direction. In the weeks between winning the aviary contract in Milwaukee and starting the actual work, I approached my two local zoos, Brookfield and Lincoln Park, with my portfolio. Lincoln Park said they already had a muralist, Dave Rock out of Tucson, the best in the biz and he was painting murals in their aviary even as we spoke.

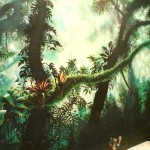

As soon as I got out of the meeting, I went to the aviary job site, which was cordoned off. I climbed over the yellow tape when none of the Zoo visitors was watching and put on a hard hat someone had left next to a lunchbox on a bench. Inside, I was adrift in a sea of huge, startlingly realistic murals. After marveling at the work for a while, I remembered my purpose. I found Dave on the other side of some zoo mesh applying a jungle to an exhibit wall with a spray gun in either hand. I introduced myself, explained what I was up against in Milwaukee and showed him my portfolio of residential murals. He was the very soul of magnanimity, reassuring me that my chops were equal to the task but explaining the logistical factors I had probably not considered. He showed me his choice of materials and equipment and demonstrated how he used them to get such photographic quality. More than anything, he gave me the confidence that I needed to do the job.

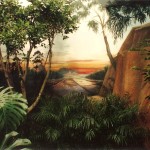

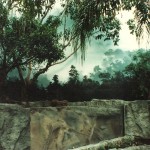

It took five months to complete Milwaukee’s aviary. At the end of it, the staff was sufficiently pleased that they began recommending me to other zoos. That, and the new mural photos of such a variety of environments — dense rainforest, Atlantic beaches, African savanna, swamps, the Arctic — gave me a starter portfolio to show other zoos what I could do. The job also gave me experience and confidence at matching the colors and texture adjacent to the mural surface so as to obscure the juncture between three-dimensional and two-dimensional features.

I was in the uncomfortable position of competing directly with Dave for future zoo jobs. But I had a family to feed and could not say no to a work offer. Although Dave’s techniques got me started, I’ve since evolved my methods and equipment in order to more efficiently, and so hopefully more affordably, get a quality image on the wall. I’m probably the fastest muralist alive, but I think Dave is still the best in the biz.

I cringe when I think back on the conditions associated with that job. I was in debt and recovering from a divorce. I tried to keep my living expenses to a minimum so as to maximize what I could keep. I sublet a dismal basement room in Milwaukee in a house being rented by some college students; it could’ve been used as the set for a slasher movie. I ate breakfast and dinner cold, out of cans (one never fully recovers from the impact of C-rations), and had a sandwich for lunch while working. I put in 12- to 14-hour days and went home to a town near Kankakee on the weekends to sleep.

The college kids upstairs were of the party persuasion, and for Halloween they were planning a drunken extravaganza for their frat brothers. They knew where they could find a casket in the back of an abandoned ambulance on a vacant lot in the neighborhood and wanted to capture it for their beer cooler. This was not Milwaukee’s most up-tone neighborhood.

They assumed no one owned the casket but were worried about neighbors reporting them to the police for absconding with a suspicious-looking object. Knowing I had some military experience, they asked my advice. I told them how a Special Forces A Team would probably go about doing a prisoner snatch. And so, at “zero dark thirty” one night — that is, sometime between midnight and dawn — they drove, dressed all in black, without headlights, to the vacant lot. Using only hand signals and no flashlights, they sent lookouts to each avenue of egress, had one up a tree in the so-called God position, and assigned the strongest men to the casket snatch. Fortunately the thing was empty. The next day after work they proudly displayed the grey, rusted metal centerpiece of their party in the basement, thanking me excessively for their great adventure. I like to help today’s wayward youth when I can. I sometimes wonder what became of those kids. I expect to see their pictures on the local Post Office walls some day.

Subsequent jobs for Milwaukee have included the Apes of Africa exhibit, the adjacent Tikal monkeys exhibit, the Small Mammals exhibit, the Lion House and the Australian building, and my Mostly True Tale about the Australian job, Boomer.

- Shorebirds exhibit in the Aviary at Milwaukee County Zoo